Two-way Streets

Forging the Paths Towards Participatory Civic Technology

By Diana Nucera

How can we make civic technology more participatory? How do we create environments in which it can thrive?

As technology becomes further integrated into our systems of governance, the challenges of our Nation’s digital divide are increasingly apparent. In Detroit, for example, social services such as social security, welfare, and unemployment have transitioned to being offered exclusively online. While this has most likely cut costs (by streamlining the services themselves), it has also cut access: According to the 2013 US census, 33% of households in Detroit lack a persistent connection to the Internet. Without the ability to interface with essential government services, those who are already disenfranchised may find themselves in dire situations, leading to crime, violence, and ultimately the destruction of their own neighborhoods.

The advent of the internet brings with it myriad opportunities to unlock the enormous potential that is otherwise latent in our local communities. These opportunities can only be sustainably seized, however, if networked technology projects are led by people who are deeply invested in their community’s welfare; that is, people with a deep understanding of—and a desire to maintain—the fabric that binds their community together.

There are many ways that civic designers can lower the barriers between those who see and wish to leverage the potential of civic technology and those who wish to galvanize their local communities. Drawing upon my experience working with the Detroit Digital Justice Coalition and Detroit Future Schools, I’ve distilled some of the most salient processes that civic technologists can use to forge a participatory digital future.

Rules of the road

My involvement with bridging the worlds of community and technology began in the Summer of 2009, when the Detroit Digital Justice Coalition came together to understand the role that media and technology might play in restoring our community and creating local micro-economies. Detroit Digital Justice Coalition is comprised of thirteen member organizations; together, they represent seniors, youth, environmental justice communities, welfare rights activists, hip hop community organizers, independent technologists, and designers. Everyone involved believes that communication is a fundamental human right.

To develop a common understanding of the role media might play, the coalition asked members to answer the following questions:

- How are you currently using media and technology for organization and economic development?

- What kind of support and collaboration would make your work stronger?

- What should digital justice in Detroit look like?

Interviews were recorded and later edited before being debuted at the first Detroit Digital Justice Coalition meeting. Attendees were then asked to write down any quotes that stood out and thoughts that emerged while listening to the highlight reel. A group conversation followed, from which the Detroit Digital Justice Principles were born, creating a unifying definition of what digital justice means to the community. They include:

Access

- Digital justice ensures that all members of our community have equal access to media and technology, as producers as well as consumers.

- Digital justice provides multiple layers of communications infrastructure in order to ensure that every member of the community has access to life-saving emergency information.

- Digital justice values all different languages, dialects and forms of communication.

Participation

- Digital justice prioritizes the participation of people who have been traditionally excluded from and attacked by media and technology.

- Digital justice advances our ability to tell our own stories, as individuals and as communities.

- Digital justice values non-digital forms of communication and fosters knowledge-sharing across generations.

- Digital justice demystifies technology to the point where we can not only use it, but create our own technologies and participate in the decisions that will shape communications infrastructure.

Common ownership

- Digital justice fuels the creation of knowledge, tools and technologies that are free and shared openly with the public.

- Digital justice promotes diverse business models for the control and distribution of information, including: cooperative business models and municipal ownership.

Healthy communities

- Digital justice provides spaces through which people can investigate community problems, generate solutions, create media and organize together.

- Digital justice promotes alternative energy, recycling and salvaging technology, and using technology to promote environmental solutions.

- Digital justice advances community-based economic development by expanding technology access for small businesses, independent artists and other entrepreneurs.

- Digital justice integrates media and technology into education in order to transform teaching and learning, to value multiple learning styles and to expand the process of learning beyond the classroom and across the lifespan.

Detroit’s Digital Justice Principles continue to serve as our Coalition’s guiding light. Perhaps more important, however, was the way in which the act of their creation united previously disparate sectors of grassroots work. The facilitation process that led us here amounted to:

- Play the audio track (the one highlighting results from our previous questionnaire).

- Ask people to write down their thoughts as they listen.

- Ask participants to further refine their thoughts using the prompt: “Digital justice is…”

- Post phrases that include the prompt in a central location for everyone to see.

- Begin a collective editing process by grouping phrases into common themes.

- Discuss each theme and identify its underlying concepts.

- Draft supporting language for those concepts from participants’ phrases.

- Assign a participant or group of participants to finalize the language.

The Detroit Digital Justice principles have since shaped several projects in Detroit and around the world, including Detroit Future School, Detroit Future Media, Detroit Future Youth, Co-Open, Code for Detroit, Digital Stewards, and several international wireless mesh networks, including the concept of DiscoTechs (Discovering Technology events).

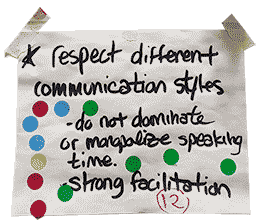

Look for desire paths

The Detroit Digital Justice Coalition’s experience underscores the importance of convening conversations throughout the creative process. More specifically, it implies that civic technologists should begin by identifying communities that are already working on difficult problems. Having identified such communities, our next task is to use participatory frameworks to help members of that community articulate their most pressing questions and sketch the shape of their answers. Then, and only then, should we introduce technology.

This process is incredibly nuanced, so let’s step through it together: Participatory frameworks help designers work with communities to articulate big questions. Big questions, in turn, offer avenues for more focused investigation.

The Detroit Future Schools Guide to Transformative Education details a participatory framework for eliciting big questions. While it was originally conceived for use in the classroom, we’ve had good success using it to work with communities. Briefly, it entails:

- Identify something you want to change. Be specific and action-oriented. If your community is struggling with digital literacy, for example, articulate all of the ways in which digital illiteracy hinders progress.

- Identify skills and practices you wish to develop. Can you strengthen existing relationships while building a mesh network? Can you train new people along the way? Are there opportunities to connect people who were not connected before?

- Ask a big question. A big question is comprised of the change you wish to see (see step one) as well as the skills and practices you want to develop (see step two).

Major topic + skills or practices you want to develop = big question

Consider how the skills and practices you’ll develop will affect the change you wish to see in your community. If your topic is community-owned communications infrastructure, for example, and the skills or practices you want to develop include storytelling, your big question might be: How does a community-owned wireless network help people tell their stories? If the topic is digital access and you want to develop deeper relationships within the community, then your big question might be: What could the role of media and technology be in building new economies rooted in relationships?

This method of community-based problem solving—also known as place-based organizing—was initially brought to my attention through the work of the Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP) in New York City. CUP is a nonprofit organization that collaborates with art and design professionals, community-based advocates, policymakers and in-house staff to improve civic engagement. Their projects demystify urban policy and planning issues that impact New York communities by breaking those issues down into simple, accessible, visual explanations and tools. These tools are later used by organizers and educators all over New York City (and beyond), enabling individuals to participate and advocate for important community needs.

CUP believes that understanding how systems work is essential for community members to feel socially empowered. Damon Rich, a founder of CUP and now the Planning Director & Chief Planner for the City of Newark, has gone on to ensure that a participatory culture thrives within Newark’s City Hall. “As someone who is in between the public and the government in urban planning, it is really critical for me to know the activists in the area,” he explains. “I need to understand how the issues we are dealing with play out in the community.”

Rich understands that community members must meet each other halfway. “A lot of times when people call me with questions about zoning regulations, I find that it is really important to break down what they are facing and explain to them what action they can take that will make the most impact. Civic engagement is about building up desire.”

Shifting into high gear

In our line of work, it’s often much easier to debate the nature of problems than to embody their solutions. “Assembling a real group of people is so much harder and more powerful than a rhetorical understanding of the public,” Rich explains. “It is in the assembly of these people that you learn what it takes to gather input, and what ideas people are attached to.” But that’s when the real work begins. “It is less about having faith in good ideas, and more about how we can create a philosophy between the government and the people. There are benefits beyond achieving the objective when we do things together.”

If we want civic technology to facilitate systems of engagement, the creation of these systems must be rooted in inclusivity. It’s not enough to embed a system within a community without also giving members of that community the skills to customize, adapt, and maintain it. Place-based organizing seeks to draw connections between diverse perspectives in order to create systems and tools that are relevant, valuable, and accessible to residents.

Civic designers can serve as leaders in this process by exhibiting a desire to both learn and teach the ways in which technology can support our communities. It is vital to have an understanding of place and politics before designing civic technology; and it’s at the intersection of civic technology and place-based organizing where the magical ingredients of a participatory design culture will be found.

Like this kinda stuff?

Consider donating to help us to continue doing this work! We also encourage reader comments via letters to the editor.

Diana Nucera is a community technologist, accomplished cellist, and media maven. She’s been working in media arts and technology education for the past fifteen years. She is currently the Director of The Detroit Community Technology Project (DCTP) at Allied Media Projects.

Diana Nucera is a community technologist, accomplished cellist, and media maven. She’s been working in media arts and technology education for the past fifteen years. She is currently the Director of The Detroit Community Technology Project (DCTP) at Allied Media Projects.